Track 5: Slaughterhouse-Five

Time travel! War! Aliens! This Vonnegut classic tackles pre-and-post-war life with satire and absurdism at its core.

I have three great loves of my life: my son, my husband, and Kurt Vonnegut. The curly-mopped writer and humorist stole my heart at 17, when Slaughterhouse-Five landed on my summer reading list for AP English Lit. The prospect of summer reading was a thrill - I have always been a nerd. This book though…I had never experienced anything like it. Time travel? War? Aliens? Not new territory for anyone, really. But the way Vonnegut spun this insane-ass story, truly, was something else entirely. I could not believe I was reading this for school. This crazy book! For school!

Being exposed to Vonnegut at a pivotal age opened my eyes to new ideas and approaches to writing that previously felt too out of orbit, too strange. Certainly he isn’t the only author to write some out-of-pocket, bizzarro shit; I think of other works like A Clockwork Orange or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, both equally out there (though, perhaps, it was just a sign of the times, all of these being books of the 1960s). Vonnegut’s works consistently hit the high end of the wackadoodle meter while also weaving in morsels of highly relatable sentiment and experiences. That balance is unique unto itself.

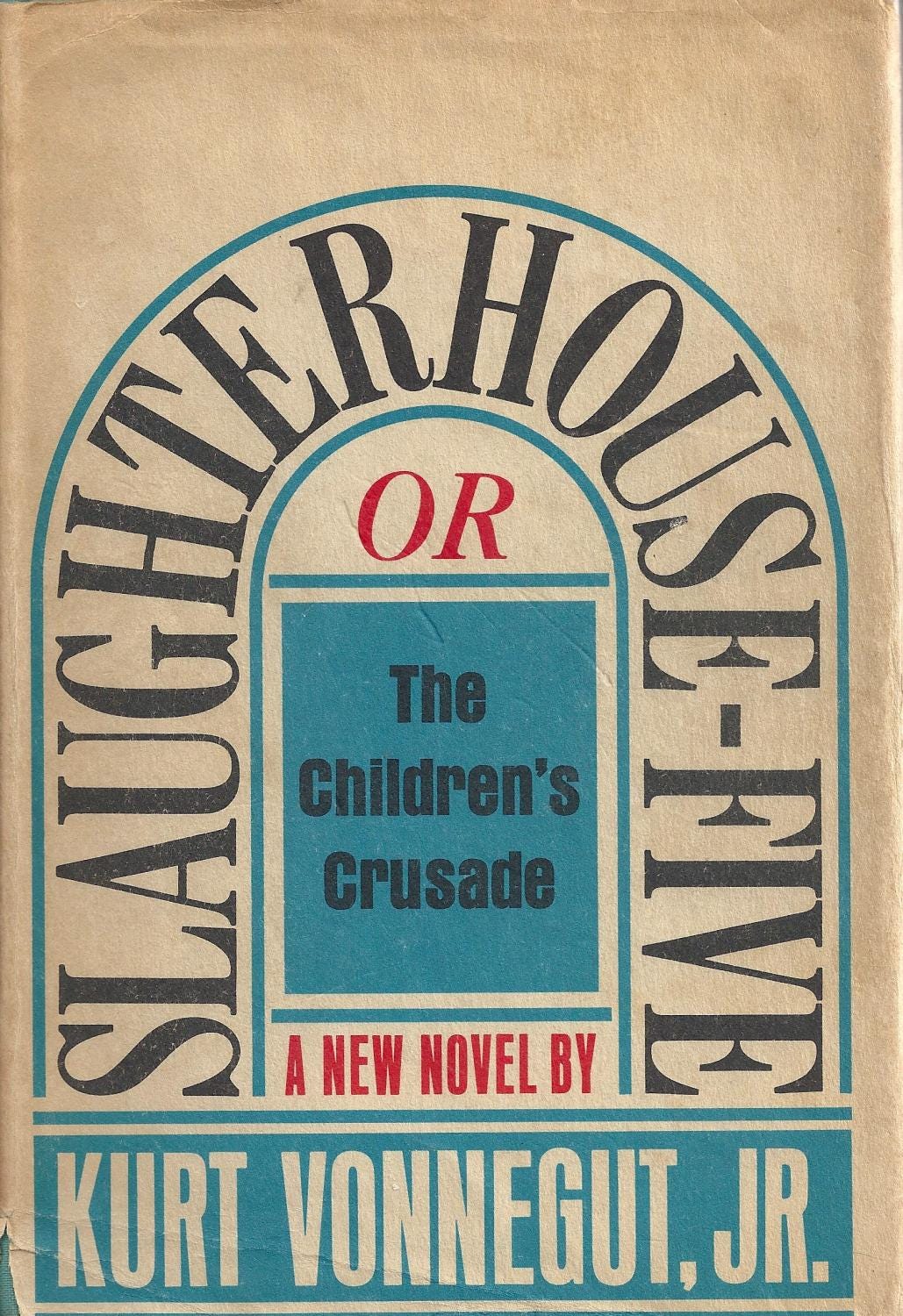

Since that fateful season of reading, Vonnegut has cemented himself as my favorite author of all time. His words donned the back of my Bachelors grad cap; his cat’s cradle illustration has a permanent home on my right forearm. Vonnegut is all, and Slaughterhouse-Five is gospel.

THE TRACK SYNOPSIS

Published in 1969, Kurt Vonnegut’s sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, takes a science fiction lens to anti-war sentiment. We follow Billy Pilgrim, a man who has become “unstuck” in time after being abducted by Tralfamadorian aliens. Through Billy’s time traveling, we witness an assortment of different periods of Pilgrim’s life from youth into old age—from his time in World War II and his survival of the Dresden bombings to his postwar life as an optometrist. Throughout the story, we are treated to critiques of war and its dehumanizing horrors, the absurdity of life in circumstances monumental and inconsequential, and the dark humor that is a hallmark of Vonnegut’s writing.

GENRE & THEMES

This book is a hard one to fit neatly into a genre. Some argue it is a quasi-autobiography, since much of the war content is based on Vonnegut’s own experiences. Others claim it as a postmodern work. To me, it is 100% a science fiction novel that folds in historical fiction.

That said, its theme are much more clear; Slaughterhouse-Five tackles a lot in its pages, but the ones that stick out again and again are:

trauma and coping (particularly in relation to wartime)

free will vs. determinism

death and mortality

the meaning of life in a world where everything feels dire and finite.

FAVORITE QUOTES

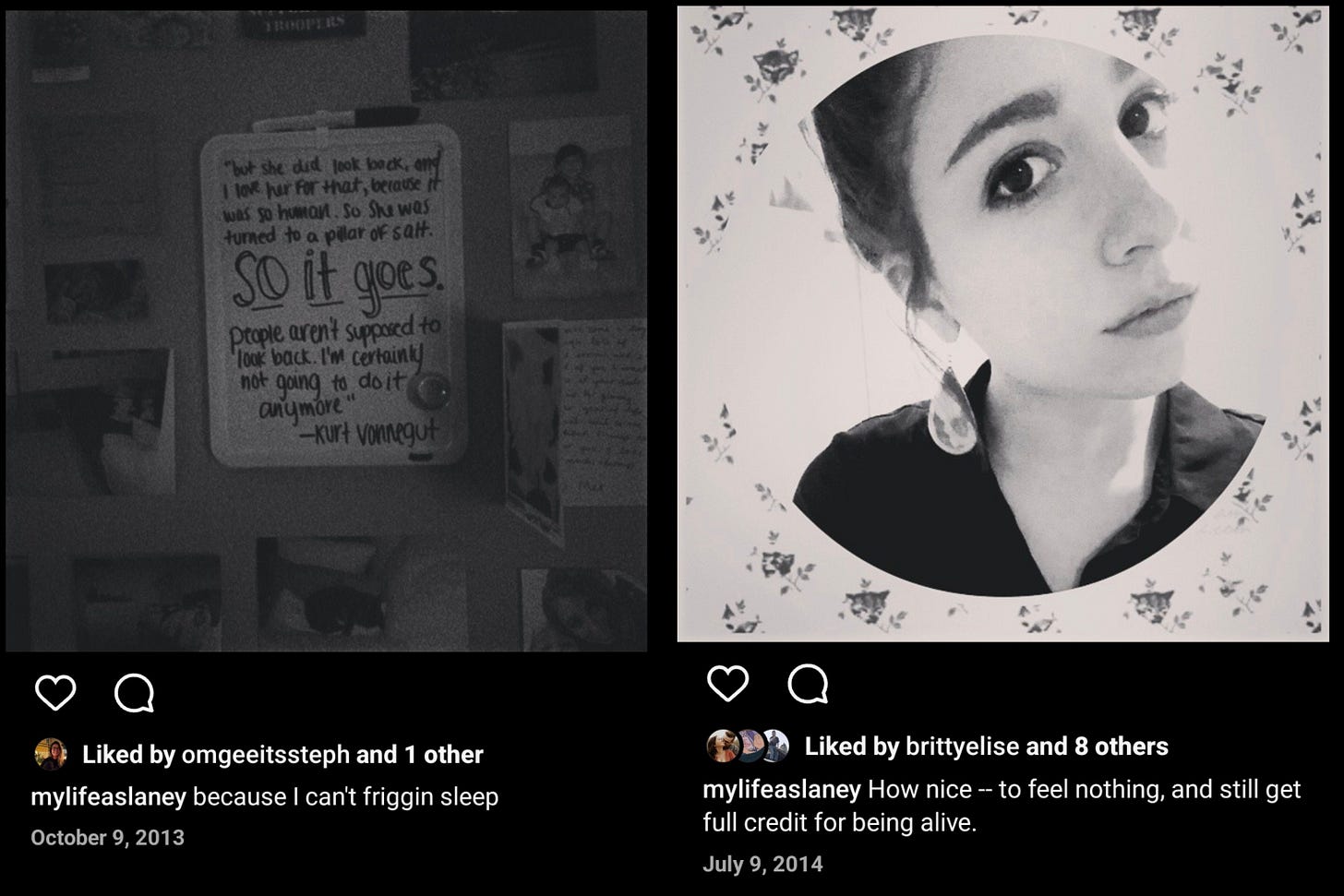

“How nice—to feel nothing, and still get full credit for being alive.”

“But she did look back, and I love her for that, because it was so human. So she was turned into a pillar of salt. So it goes.”

“Well, here we are, Mr. Pilgrim, trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why.”

“Everything is nothing, with a twist.”

THE ARTIST BIO

Vonnegut was born in 1922 in Indianapolis, Indiana, the youngest of three coming of age through the Great Depression; the hardships his family faced—coming from money only to lose so much—shaped a great deal of his worldview. After high school, he enrolled at Cornell University, opting to study biochemistry despite his disinterest and indifference toward the subject. He eventually dropped out and enlisted in the US Army, where he served in World War II and survived the devasting Dresden bombings, eventually becoming a prisoner of war. After his evacuation and discharge from the US Army, he returned to the states and picked back up on the writing that he reveled in during his Cornell extracurricular activities. He went on to earn a Masters in Anthropology from the University of Chicago, where his novel Cat’s Cradle was accepted in lieu of a Masters thesis. In his lifetime, Vonnegut wrote 14 novels, including well-known works Breakfast of Champions and, of course, Slaughterhouse-Five, as well numerous short fiction collections, non-fiction essays and collections, and plays. He had 3 biological children and 4 adopted children, and two wives, both of whom are interesting people on their own. Vonnegut died at 84 years old in 2007.

DECONSTRUCTING THE TRACK

I have talked about Slaughterhouse-Five so much over the past 16 years, I’m surprised that my head hasn’t popped off. I’ve plastered notes and drawings and Instagram captions with quotes from this book. I’ve uttered the phrase, “Have you read Slaughterhouse-Five?” so many times that it should be a crime. Anyone who would listen to me for more than five seconds would get my well-rehearsed laudation of Vonnegut and this specific novel. Exhibit A: a guy I saw on and off for years heard me talk about Slaughterhouse-Five so often that he asked to borrow my copy (the one from high school with all of my notes and thoughts etched in the margins); when we had our penultimate fight at the end of undergrad, my parting line was: “I want my damn Vonnegut back.” When he finally mailed it to my parents’ house a year later, all he could say was, “yeah, you were right. That book was awesome.”

I’ve read and re-read Slaughterhouse-Five, but I find that the more I read it, the less the plot itself speaks to me and the more certain passages or quotes evoke an emotion. What hits me square in the chest is his way of bluntly putting complex emotions into tangible thoughts and phrases. “So it goes” is undoubtedly the most popular, well-known quote from this book (another person I dated in college had it tattooed on his bicep). Despite that, the sentiment that it conveys—"it is what it is” meets “such is life”—is something everyone has felt or will feel in their lifetime. How powerful is it that Vonnegut was able to distill that feeling down into a three-word phrase?

An aspect of the book that continues to stick out to me, too, is the balance between autonomy and determinism. Billy truly believes in free will, in one’s own volition, while his captors, the Trafalmadorians, firmly believe in fatalism, with morality being meaningless and fate always leading the way. In my life (as I’m sure is the case for others), I have been both Billy Pilgram and the Trafalmadore. I have felt that we determine our own lives and outcomes, and I have also felt like things are how they are because it is predetermined and unalterable. Sometimes I still feel that pull from one side or the other, that shift coming day-to-day, lived-experience to lived-experience. That I could find those warring points of view in the pages of this book serves as validation, and perhaps confirmation, that these feelings can exist at once. Both can be true. Neither can be true. And ultimately, that’s okay.

At this moment in time, I’m not sure I feel one way or another about the afterlife, but I hope that if a place exists where everyone congregates after they’re gone from the mortal plane, Vonnegut is there. There is nothing more that I would like to do than find him in that Elysium, have a cup of coffee, and shoot the shit. Sounds like heaven to me.

Thank you for listening.